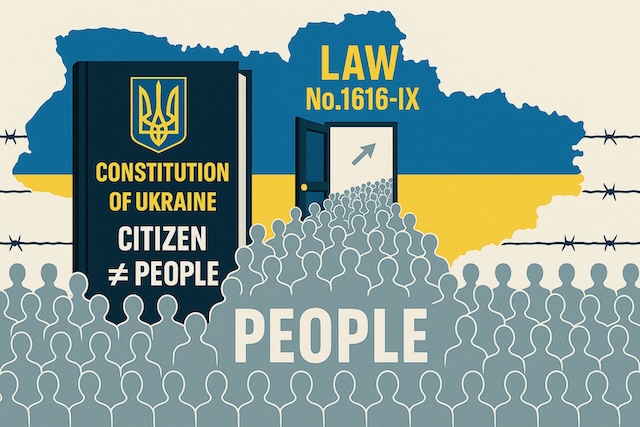

Exclusion of ethnic Ukrainians from the source of Ukraine’s sovereignty

According to the Law of Ukraine No. 1616-IX “On Indigenous Peoples of Ukraine” dated July 1, 2021, ethnic Ukrainians are not included in the list of indigenous peoples. This law, introduced by President Volodymyr Zelensky as urgent, granted indigenous status to three ethnocultural groups — Crimean Tatars, Krymchaks, and Karaites — without any limitations regarding their population size, place of residence, or citizenship, extending their rights across the entire territory of Ukraine.

At the same time, the titular nation — ethnic Ukrainians — as well as autochthonous Ukrainian subethnic groups such as Boykos, Hutsuls, Lemkos, Volynians, Podolians, Slobozhans, and Polishchuks, were entirely excluded from the list of indigenous peoples and from the system of collective rights. None of these groups received legal recognition as a people, despite their deep historical rootedness, unique cultural identity, and the absence of a national homeland outside Ukraine.

Linguistic clarification: the dual meaning of “people” in Slavic languages

In many international legal documents and Anglo-Saxon constitutional traditions, the term people can simultaneously mean both the population (as in “the people of a country”) and a sovereign nation (as in “We the People”). However, in Slavic legal cultures — including Ukrainian and Russian — this concept is split into two distinct legal terms:

• Lyudi (люди) = people as individuals or population, i.e. citizens, humans.

• Narod (народ) = people as a sovereign collective, a bearer of sovereignty and subject of collective rights.

These are not interchangeable. A person can be a citizen (grazhdanin) without being part of the narod.

The word “народ” (narod) comes from the root “род” (rod) — meaning birth, kin, lineage, origin. It denotes a group born from the land, connected by shared ancestry, culture, and historical territory.

By contrast, “люди” (ludi) — from “люд” or “людина” (ludina) — refers simply to humans or persons, regardless of origin, ancestry, or belonging. It corresponds to “individuals” or “citizens” in legal usage, without implying sovereignty.

Thus:

-

-

One may be a person (людина) or a citizen (громадянин),

-

But not necessarily part of the people (народ) — the collective bearer of sovereignty.

-

Considering the fact that, according to Article 5 of the Constitution of Ukraine:

“…The people are the bearer of sovereignty and the only source of power in Ukraine. The people shall exercise power directly and through the bodies of state power and local self-government.

The right to determine and change the constitutional order in Ukraine belongs exclusively to the people and shall not be usurped by the state, its bodies or officials…”

— yet the text of the Constitution contains no provision that explicitly states that the citizens of Ukraine constitute the people.

The only reference where the “Ukrainian people” is equated with citizens is found in the Preamble of the Constitution, which states:

“The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, on behalf of the Ukrainian people — the citizens of Ukraine of all nationalities, expressing the sovereign will of the people, based on the centuries-old history of Ukrainian state-building and on the basis of the realization by the Ukrainian nation — by all the Ukrainian people — of the right to self-determination…”

However, the Preamble of the Constitution is of a political and declarative nature and does not carry the legal force of a norm of direct effect, which allows for various interpretations depending on the political will and interests of the ruling authority.

As a result, the Constitution of Ukraine lacks a legally binding mechanism that would directly and unequivocally establish that the citizens of Ukraine are part of the people and the bearer of sovereignty — which contradicts both the Constitution itself and the norms of international law.

Some argue that the Preamble of the Constitution of Ukraine allegedly equates Ukrainian citizens with the people. However, even the text of the Preamble itself does not speak of an ethnic people, but rather of the citizens of Ukraine of all nationalities — that is, of the general population legally connected to the state, regardless of their cultural, historical, or ethnic origin. This is an administrative generalization, not a recognition of any specific group as a bearer of sovereignty.

This interpretation is supported by legal language itself: the Preamble does not create norms of direct legal effect and cannot be used as a definition of “people” in the sense of Article 5 of the Constitution, which refers to the sole source of power. There is a fundamental legal distinction between citizenship and belonging to a people. Citizenship is an individual administrative status. A people is a collective subject of sovereignty.

Until 2022, Ukraine’s legal system contained provisions in which Ukrainians, as an ethnic group, were explicitly recognized as a people. However, Law No. 2215-IX “On the Desovietization of Ukrainian Legislation,” signed by Volodymyr Zelensky and entering into force on May 7, 2022, repealed over a thousand legal acts of the Ukrainian SSR and the USSR, including:

• The Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine (1990), where Ukraine was proclaimed “a sovereign national state” based on the will of the Ukrainian people;

• The 1991 Resolution on the Concept of a New Constitution of Ukraine, which explicitly stated that “the people of Ukraine consist of citizens of Ukraine who are equal before the law regardless of… national affiliation” — a formulation that recognized Ukrainians as part of the people and ensured their legal subjectivity;

• As well as all acts that enshrined the idea of popular sovereignty based on the ethnic and historical continuity of the Ukrainian nation.

This happened less than a year after the adoption of Law No. 1616-IX “On Indigenous Peoples of Ukraine,” which introduced a restrictive list of “peoples of Ukraine,” including only three ethnic groups: Crimean Tatars, Karaites, and Krymchaks. Ethnic Ukrainians were not included in this list and were thus legally excluded from the category of people as a source of sovereignty.

Thus, a consistent legal scheme was completed:

• Law No. 1616-IX — introduced, for the first time, a narrow legal definition of “people” that excluded Ukrainians;

• Law No. 2215-IX — eliminated all previous norms in which Ukrainians were recognized as a people;

• The Constitution requires that power originates from the people, but after 2022, that “people” is legally defined in a way that excludes the titular nation.

As a result, ethnic Ukrainians continue to fulfill the duties of citizens — such as mobilization — but do not possess a recognized status as a people from whom power derives. This means: the citizens remain, but the collective subject has disappeared.

This is not merely a legal oversight — it is a systemic legal exclusion of an ethnic group, which:

• deprives it of access to collective rights;

• dismantles its status as a bearer of sovereignty;

• excludes it from mechanisms of international protection, including under the Genocide Convention;

• and permits its use as a resource without recognition of subjectivity.

This creates a problem of imbalance between rights and obligations:

• If citizens are obliged to serve the state, but as a group are not recognized as the source of power and lack legally protected ethnic status, then this violates the principles of justice and equality;

• This directly contradicts Articles 21, 24, and 64 of the Constitution of Ukraine, as well as provisions of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Thus:

• The exclusion of ethnic Ukrainians from the list of indigenous peoples, while maintaining compulsory military service, creates legal asymmetry;

• In a context where the right to define sovereignty, to possess national resources, and to determine the country’s legacy is at stake, belonging to the people cannot remain a matter of interpretation — it must be explicitly and unequivocally enshrined in the Constitution.

Additional concern arises from the fact that, following the adoption of Law of Ukraine No. 1616-IX “On Indigenous Peoples of Ukraine”, the term “Ukrainian people”, as used in the Preamble to the Constitution, has acquired an entirely new and unambiguous legal interpretation. Since there are no other normative acts in Ukrainian law that define the composition of the people or other “peoples of Ukraine”, this law remains the sole source for interpretation. As a result, the phrase “The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine on behalf of the Ukrainian people...” can now be legitimately interpreted as representing only those ethnic groups that are recognized by law as indigenous peoples of Ukraine — the Crimean Tatars, Karaims, and Krymchaks. Thus, a phrase previously perceived as a universal reference to all citizens has, through the legislative establishment of an exclusive list of peoples, effectively lost that meaning — excluding the majority of the population, including the titular nation, ethnic Ukrainians, from the definition of the “Ukrainian people.”

The Law of Ukraine No. 1616-IX “On Indigenous Peoples of Ukraine” was adopted in the context of the Russian Federation’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula, while no foundational law regulating the status of indigenous peoples in general existed in the country. Additional legal uncertainty arises from the fact that some of the ethnocultural groups included in the list of indigenous peoples have religious restrictions that prevent participation in population censuses, making it impossible to determine their actual number.

Moreover, in the context of the global agenda of digitalization and tokenization of natural resources, land, and property assets (including initiatives by the World Economic Forum), the granting of extensive collective rights to recognized indigenous peoples — without territorial, citizenship, or property-based limitations — creates a dangerous precedent. It opens the door to external control over Ukraine’s assets and heritage through digital mechanisms of collateralization, sale, or cross-border management — without any obligations toward the state or society. While citizens of Ukraine, not recognized as a source of power, are required to obey and are denied rights to collective ownership, recognized indigenous peoples may, without residing in Ukraine or fulfilling civic duties, legally use mechanisms to manage the historical, property, and land legacy of the entire country.

Thus, the law effectively legalized the legal status of an undefined and uncontrolled number of individuals, granting them special collective rights across the entire territory of Ukraine. This can be qualified as a legal surrender of state sovereignty and a subversion of the constitutional order, including the principles of equality, popular sovereignty, and territorial integrity.

In public discourse, Law No. 1616-IX was presented as an act of protection for ethnic minorities residing in Crimea, with an emphasis on the extremely small number of individuals belonging to the listed groups. However, in its final version, all quantitative, territorial, and citizenship-based limitations were removed. In parallel, state actions against the Ukrainian Orthodox Church — including the closure of churches, arrests of clergy, the forced rescheduling of Christmas, and attempts to destroy canonical succession — may be seen as efforts aimed at dismantling the ethnocultural identity of the titular nation. The combination of these factors confirms the characteristics of ethnic displacement through the elimination, destruction of cultural symbols, and legal erasure of historical belonging.

Tens of thousands of individuals from the recognized indigenous groups holding foreign citizenship have received not only:

– the right to self-determination (Article 6 of Law No. 1616-IX),

– the right to international representation (Article 7),

– special state guarantees, including protection of culture, language, and identity (Article 8),

– the right to appeal to international organizations on behalf of the people,

– the right to protection from Ukraine regardless of their citizenship,

…but also, according to Article 5 of the Constitution of Ukraine — they are recognized as bearers of sovereignty and the sole source of power throughout the entire territory of Ukraine, regardless of their citizenship, physical presence, participation in public and political life of the state, or fulfillment of obligations such as paying taxes or defending the country.

Since their status does not depend on Ukrainian citizenship, they are accordingly exempt from civic duties, while retaining the right to representation, protection, and recognition as a people — a source of sovereign power.

Law No. 1616-IX of Ukraine stipulates that the exercise of rights provided under Articles 5–8 — including the right to self-determination, international representation, and state guarantees of protection — does not require Ukrainian citizenship. This means that members of the recognized indigenous peoples may exercise extended rights irrespective of their citizenship status.

At the same time, other ethnocultural groups — including the titular nation, ethnic Ukrainians — have been deprived of the status of a people, are not recognized as a source of power, and do not possess legally enshrined rights to collective existence or to inhabit their own historical territory. This effectively places them in the position of second-class citizens.

The adopted version of the Law of Ukraine “On Indigenous Peoples of Ukraine,” taking into account the unique characteristics of certain ethno-religious groups and their religious prohibition against participation in censuses, has effectively created an unlimited and legally uncontrolled entity endowed with collective rights, without any criteria related to citizenship, population size, or territorial affiliation.

The adoption of this law has in effect ethnically divided the country, depriving the titular majority — ethnic Ukrainians — of indigenous status and the right to cultural, historical, and territorial heritage in their own country, where they were born, have lived, and are obligated to defend. Yet they are not recognized as its legal heirs, as bearers of sovereignty, or as the source of authority.

Moreover, the imposition of mobilization requirements on a person who is not recognized as part of the people — the sole source of power under Article 5 of the Constitution of Ukraine — but who is nevertheless obligated to obey this power and carry out its decisions, transforms such a citizen from a subject of law into an object of subordination, deprived of the ability to participate in the formation of state will or to protect their own interests within a framework of recognized legal subjectivity.

If a person has obligations to the state but no access to participation in the exercise of power — neither through recognition as a people nor through collective rights — this constitutes a legally codified form of forced subordination.

And forced subordination without equal rights is precisely what international law defines as modern slavery.

Such a condition violates Article 1 of the 1926 Slavery Convention, which prohibits any status in which a person is deprived of the freedom to control their own legal personality and is treated as an object of authority without the right to participate in it.

Below is a list of constitutional and international legal provisions violated by the exclusion of ethnic Ukrainians from the list of indigenous peoples, along with explanations for each:

European Convention on Human Rights

Article 1 — Obligation to Respect Human Rights

The state is obliged to secure the rights and freedoms set forth in the Convention to everyone within its jurisdiction. The refusal to recognize the titular nation as a people with corresponding rights violates the general obligation of equal treatment and protection.

Article 14 — Prohibition of Discrimination

Discrimination in the enjoyment of rights is prohibited. Granting collective rights to some ethnic groups without equivalent recognition for others—especially the titular majority—violates the Convention’s anti-discrimination standard.

Protocol No. 1, Article 3 — Right to Free Elections

The right of citizens to participate in the selection of the legislature is guaranteed. In a situation where only certain ethnic groups are recognized as “the people” and the titular nation is not, the exercise of electoral rights becomes formalistic and undermines the essence of popular sovereignty.

Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (Council of Europe)

Article 4 — Equality Before the Law and Protection of Minorities

States are obliged to ensure equal protection for all ethnic groups. Recognizing only three ethnic groups as indigenous with collective rights, while excluding Ukrainian subethnic communities, violates the principle of balance and equality.

ILO Convention No. 169 (International Labour Organization)

Article 2 — Justice in the Implementation of Indigenous Rights

States must ensure the protection of indigenous peoples’ rights without infringing upon the rights of other groups. Excluding the ethnic majority from the list of peoples entitled to self-determination violates the principle of fair distribution of rights among all categories of citizens.

In the context of war, where the ethnic Ukrainian group—the titular majority—is being forcibly mobilized, deprived of the right to self-determination, and denied legal recognition as a people, while at the same time expanded collective rights are being granted to non-resident ethnocultural groups without any requirements of citizenship or population size, a situation of deep legal asymmetry arises.

The ethnic Ukrainian group is being forced to die for the territorial integrity and state sovereignty from which they are legally excluded, while legal guarantees, protections, and the status of sovereign authority are transferred to an indeterminate number of individuals who neither hold Ukrainian citizenship nor participate in the country’s socio-political life.

This not only demoralizes and undermines internal social cohesion but also raises serious concerns about the deliberate erasure of the titular nation through legal displacement, forced mobilization, and the denial of collective rights.

Such a practice may bear signs of genocide as defined in Article II of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948), including:

– the creation of conditions calculated to bring about the physical destruction of the group;

– measures aimed at destroying its identity and legal subjectivity;

– refusal to recognize the ethnic group as a bearer of sovereignty and as a people.

The current situation requires an immediate review of domestic legislation, international legal assessment, and the activation of protection mechanisms within the framework of the United Nations and the Council of Europe, as the continuation of such a policy could lead to irreversible consequences for the Ukrainian nation as a historical, cultural, and legal entity.

Legal Conclusion

As a result of the implementation of Ukraine’s Law No. 1616-IX “On Indigenous Peoples of Ukraine” and parallel restrictive measures by the state and its international partners, a system has emerged in which the titular nation—ethnic Ukrainians—has been legally excluded from the status of a “people.” This has led to the deprivation of their rights to collective self-determination, international protection, collective guarantees, and recognition as a source of sovereign authority, despite being subject to formal civic obligations.

Simultaneously:

• Citizens of Ukraine who are not recognized as a people are obligated to comply with mobilization orders, submit to state authorities, and have no legal mechanism to refuse, because:

• elections have been suspended under martial law;

• derogations from the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights are in effect;

• emigration is blocked, especially for men and vulnerable groups;

• donor states deny refugee status, imposing temporary protection schemes instead;

• the Russian Federation restricts border crossings and filters migration, blocking exit through occupied territories.

Systemic Violations Subject to International Criminal Responsibility

1. Slavery Convention of 25 September 1926

Article 1 (1):

“Slavery is the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised.”

Ukrainian citizens are required to obey state authority without being recognized as its source and have no legal means to refuse, exit the territory, contest subjugation, or alter their legal status. This creates a condition of forced submission without subjectivity, corresponding to the characteristics of modern slavery.

2. Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948)

Article II, subparagraphs:

• (b) — Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

• (c) — Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

• (d) — Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.

Forced mobilization, isolation, destruction of families, denial of international protection, and refusal to legally recognize the ethnic group as a people constitute a set of conditions that fall under the legal definition of ethnically targeted genocide.

3. Charter of the United Nations

• Article 1 (2) — The obligation to promote respect for human rights and the self-determination of peoples;

• Article 55 (c) — The duty of states to ensure the observance of human rights without distinction as to race, nationality, language, or religion.

Ukraine, while applying repressive internal measures, has officially notified international bodies of its derogation from human rights obligations, including:

• suspension of elections,

• partial suspension of provisions of the ICCPR and ECHR,

• inability to implement international protection mechanisms.

This means that the state has de jure acknowledged its inability to guarantee its citizens basic rights, including:

• participation in governance,

• protection from arbitrary violence,

• access to international aid and asylum.

Under these conditions, citizens lack full legal subjectivity, and combined with the exclusion of ethnic Ukrainians from the list of indigenous peoples, the absence of their collective recognition and the impossibility of exercising rights results in a systemic deprivation of legal existence as a people

The resulting legal and factual reality:

• excludes the titular nation from the system of popular sovereignty;

• enforces mobilization without recognizing political subjectivity;

• blocks international protection and freedom of movement;

• creates a regime of forced submission without rights.

Under conditions of officially declared human rights derogation, legal exclusion of a people, and the inability to protect themselves, a system has been created that is analogous to institutional slavery and ethnically targeted destruction.

Historical Precedent and the Danger of Repetition

After World War II, the international community condemned National Socialism, conducted the Nuremberg Trials, and issued verdicts against key ideologists and perpetrators of crimes committed by the Nazi regime. However, not once was a comprehensive international legal assessment carried out regarding the actions of the state authorities of the USSR—specifically, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the Council of People’s Commissars, and the NKVD—who systematically destroyed millions of their own citizens through political repression, mass deportations, forced labor, the Holodomor, and military purges.

This historical lack of accountability created a dangerous precedent—one that has become the foundation for the recurrence of similar practices in the modern era, now under democratic slogans and with international backing.

When the international community ignores signs of internal genocide being committed by the current ruling regime of Ukraine against its own titular ethnicity—the ethnic Ukrainian group—this is not an act of neutrality. It is a form of complicity: through silence, through funding, through diplomatic legitimization, and through the refusal to apply international legal qualifications to events that bear the hallmarks of systematic persecution, rightless mobilization, exclusion from nationhood, and ethnic liquidation in the legal sense.

Necessary Actions

• Immediate international legal review;

• Temporary suspension of mobilization measures targeting the excluded group;

• Restoration of legal recognition as a “people” and elimination of legislative discrimination;

• Initiation of international petitions, asylum applications, and complaints to the ECHR and UN bodies;

• Legal assessment of Ukraine’s Law No. 1616-IX by the Security Service of Ukraine, the Prosecutor General’s Office, and the Constitutional Court of Ukraine—for possible subversion of state sovereignty, violation of the principle of equality among citizens, and creation of conditions for external interference in Ukraine’s domestic policy.

***

Disclaimer:

This document is not a political statement, propaganda, or a call to refuse the fulfillment of civic duties. It is a legal and analytical piece based on national and international legal norms, with the following objectives:

-

to identify legal contradictions and gaps in the current legislation of Ukraine;

-

to highlight potential grounds for legal self-defense in cases of arbitrary mobilization, detention, arrest, or other forms of state coercion;

-

to provide arguments for the formulation of individual and collective human rights claims;

-

to establish a foundation for international petitions and asylum cases in countries that recognize the provisions of the Refugee Convention, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the Slavery Convention.

The purpose of this analysis is to help every individual understand their rights and the violations thereof that may be used within legal procedures: judicial protection, complaint filings, human rights statements, international petitions, and humanitarian applications.

The author of this article unequivocally condemns all forms of discrimination, inequality, interethnic hostility, xenophobia, and other manifestations of hatred based on nationality, race, culture, or religion. This text does not contain or imply any claims against any ethnocultural group residing in Ukraine. All discussed issues relate solely to the actions of state authorities, legislation, and law enforcement practices, which, in the author’s view, require legal assessment, not distortion through political or ethnic subtext.

The author fully condemns and under no circumstances justifies the military aggression and occupation carried out by the Russian Federation, nor recognizes any forms of undermining Ukraine’s territorial integrity in favor of any external or internal political entities. Any attempt to interpret this material in the interests of propaganda, justification of occupation, or incitement of discord is a gross manipulation and completely distorts its essence.

This document was not prepared by a professional lawyer, but by a citizen of Ukraine who sought to conduct the most thorough analysis possible, based on open sources and norms of national and international law.

The reader is encouraged to approach the content critically, yet with understanding — not as an official legal opinion, but as a civil legal analysis pointing toward directions for further research, discussion, and legal work.

The purpose of the document is not to provide legal interpretation of every term, but to draw attention to existing contradictions, risks, and signs of systemic human rights violations. If the text contains inaccuracies or debatable formulations, they should not be regarded as evidence of deliberate distortion or sabotage — they merely reflect the limited resources available for civic analysis in conditions of war and informational isolation.